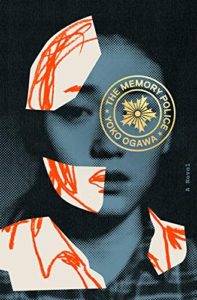

The Memory Police by Yōko Ogawa (translated by )

The Memory Police by Yōko Ogawa (translated by )

(Pantheon, Random House August 13, 2019)

Reviewed by Renae Lucas-Hall

This internationally-acclaimed writer transports you to a disturbing dystopian island where everyone and everything gradually disappears, leaving its vulnerable inhabitants at the mercy of a terrifying totalitarian regime.

Imagine, if you will, waking up knowing something seems strange, eerie and definitely off, but you’re not sure what’s bothering you. Still unsure a few hours later, you chat with your neighbors and you collectively realize all the bells have been removed from your island, or the ribbons have been removed from drawers, or even worse the birds have disappeared from the sky. Adding to the peculiarity, you don’t feel any emotion, sentimental longing, or nostalgia. It’s as if the bells and ribbons and birds never existed in the first place. Despite your complacency, you know life is a living hell for those unlucky few who still feel attached to anything that has vanished. They hide away knowing they’ll be hunted down by the Memory Police and removed from society for remembering the value of anything that dematerializes. This is the premise of Yōko Ogawa’s latest book, originally published in Japanese in 1994, and now expertly translated into English by Stephen Snyder.

Ogawa has won nearly every literary prize Japan has to offer and her popularity is up there with Haruki Murakami thanks to her gentle prose, the detailed portrayal of her characters, and gripping plots which are written with conviction and precision. Fans of Murakami will see similarities in Ogawa’s writing style and the way she interweaves fantasy with reality but they’ll also appreciate her softer and more delicate approach. Onion skins are described as butterfly wings and the finger nails on a child are likened to flower petals as they flutter to the floor, soft and transparent.

Some say Murakami and Ogawa owe their huge international appeal to the lack of Japanese cultural references in their books and the fact Western food, lifestyles, and ideologies are entrenched in most of their stories. This isn’t entirely true: The characters in this book maintain their sense of what it is to be Japanese. You can’t help but groan and feel uneasy, along with the unnamed narrator, when the Memory Police fail to remove their shoes at the entrance to her home and stomp all over the tatami flooring, knowing this is a definite no-no in Japan. The narrator also offers friends her Japanese-style room when they need somewhere to stay, confirming her inner need to maintain omotenashi (authentic Japanese hospitality) even in extreme circumstances. Green tea is served and fish is steamed in sake. An old lady at the market wears work pants fashioned out of kimono material, an earthquake strikes the island (a common occurrence in Japan), and when the roof of the old man’s boat gets sucked under the sea Ogawa describes it as folding like origami, proving once again the author cannot escape her desire to write stories with ties to Japan.

Ogawa explores kindness, benevolence, vulnerability, and death in this novel. It not only makes you wonder how you feel about others, it’s also about how much you’re prepared to sacrifice and whether you’d extend a helping hand to people you don’t know well. The narrator, a novelist, risks her life to hide her editor from capture, she fills an old lady’s basket full of celery when food is scarce because her situation is so sad, and she takes in the next-door neighbor’s dog when its owners are arrested. Her mother is also taken away and dies at the hands of the Memory Police when she’s a child and this loss stays with her throughout the book.

When the narrator is faced with the possibility of something terrible happening to her friends, the old man and her editor, she’s unable to control her emotions and bursts into tears. Her youth and naivety make her feel inherently weak but her caring editor explains these tears are a point of strength and encourages her to take solace in the fact that if you look deep within yourself, you can find enormous power and fortitude in difficult circumstances.

“I think all this crying must be proof that my heart is so weak that I don’t know how to help myself.”

“But I’d say it’s just the opposite. Your heart is doing everything it can to preserve its existence. No matter how many memories these men take away, they’ll never reduce it to nothing.” (pg. 158)

This novel also brings to mind Anne Frank who writes a diary to express her fears, disappointments, thoughts, and feelings while she hides in an attic apartment in Amsterdam during World War II. Similarly, the narrator here is trying to complete a novel about a singer trapped by her sadistic typing teacher in a room with no access to the outside world where she loses all sense of what it is to be herself.

This book makes you think on a deeper level and not just about who the Memory Police are and why all these people feel nothing when everything in their lives is disappearing. It prompts you to reconsider what truly matters to you and who is important in your life.

Ogawa has a brilliant way of appealing to your five basic senses whenever her characters are feeling traumatized. The Memory Police are described as having forceful, rhythmic boots. You can almost see and hear them marching strictly in unison, dreading every step as they pass. At their headquarters, the officers pace back and forth

“but no voices could be heard, no sound of laughter. Nor was there any music playing. Just the ringing of heels against the hard floor.” (p. 102)

It’s profoundly disconcerting. Your reading pace accelerates and your heart beats faster as you picture every intimidating scene focusing on these authoritarian law enforcement officers, inhumane and devoid of any shred of sympathy. Ogawa wants you to see, hear, and feel all of this terror and tension. She reaches into the inner-workings of the psyche and probes your feelings and emotions as you consider the harrowing psychological impact of each scenario on her characters.

Several questions remain unanswered at the end. This may bother some readers when they reach the final page, but do you really need every story to finish tied up in a neat little bow? The Memory Police leaves you with fundamental moral and political questions. Great books make you think laterally and give rise to discussion. This novel does exactly that. It’s one book you’re unlikely to ever forget.

About the Reviewer

Renae Lucas-Hall is an Australian-born British novelist and writer at Cherry Blossom Stories. She completed a B.A. in Japanese language and culture at Monash University and an Advanced Diploma in Business Marketing at RMIT University. She is the author of Tokyo Hearts: A Japanese Love Story (2012, ranked number one in Coming of Age books on Amazon Japan) and Tokyo Tales: A Collection of Japanese Short Stories (2014). Connect with Renae on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Visit her website cherryblossomstories.com.

About the Author

Yōko Ogawa’s fiction has appeared in The New Yorker, A Public Space, and Zoetrope. Since 1988 she has published more than twenty works of fiction and nonfiction, and has won every major Japanese literary award.

More books by Yōko Ogawa:

The Housekeeper and the Professor