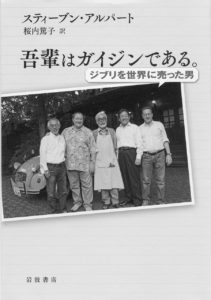

(Photo of author, left, with Hayo Miyazaki and others)

An excerpt from the upcoming release By Steve Alpert

Temporarily Misplaced in Translation

When I first began learning Japanese I was struck by how beautifully it can express certain things in a way that’s different from how they might be expressed in English, and by how things that aren’t normally expressed in English can be expressed in Japanese. My idol was the Columbia University professor Burton Watson, whose translations of Chinese and Japanese poetry and fiction were the best. My dream was to have a career like his. That was before I learned that he had quit teaching to become a taxi driver. Also before I ever attempted to seriously translate anything.

When I first began learning Japanese I was struck by how beautifully it can express certain things in a way that’s different from how they might be expressed in English, and by how things that aren’t normally expressed in English can be expressed in Japanese. My idol was the Columbia University professor Burton Watson, whose translations of Chinese and Japanese poetry and fiction were the best. My dream was to have a career like his. That was before I learned that he had quit teaching to become a taxi driver. Also before I ever attempted to seriously translate anything.

Translating from Japanese to English or from English to Japanese is very hard. For a lot of reasons the two languages simply don’t line up right. Even the best translators are often performing a metaphysical leap of faith. Japanese is very vague. And English, a Germanic language, is more precise.

The scene in Sofia Coppola’s film Lost in Translation where Bill Murray’s translator keeps relaying the director’s complex instructions simply as “talk louder” is not atypical. In the movie business translations are never checked by anyone. You’re the translator, you say this is how it should be done, and that’s it.

One of my Japanese literature professors told me that as a graduate student he once moonlighted doing translations. In an American film he came across the phrase “like a bull in a china shop.” He thought the phrase meant “a bull in a store owned by a Chinese person,” and that’s how it appeared up on the silver screen. Because movie translations in Japan are never checked by anyone, the subtitles of every translated film have at least one bull in a Chinese person’s store in them. Whenever I went to the movies to see an English-language film in Japan I always found the audience laughing at something that wasn’t supposed to be funny, or I would be the only person in the theater laughing at something that was supposed to be funny but that no one else got because it wasn’t translated right.

When I was asked to start translating Ghibli’s films into English, I wanted to do better than that, and I was immodest enough to think that I could. As Groucho Marx once said, you should never criticize a person’s work until you’ve walked a mile in his shoes. If he gets mad, you’ll be far away and you’ll have his shoes.

These are some of the things I learned translating Ghibli’s films from Japanese into English:

Rule 1—Don’t release your translation until you find out what it’s going to be used for

Toshio Suzuki called me up one day in my office at Shinbashi shortly after I had joined the company and asked me if I would mind translating something for him. It was a summary description of the new film Princess Mononoke and was written in very flowery, poetic language. It had been written by Hayao Miyazaki for the composer Hisaishi Joe to help him get a feel of the mood of the film so Hisaishi could work on the film’s music. The film was still in production at Studio Ghibli and I had only a very sketchy idea of what it was about.

I immersed myself in the text and let myself feel the atmosphere that it created and then came up with a translation. It wasn’t polished or carefully considered. It just more or less conveyed what I thought the meaning of the original was, in English.

I faxed my translation back to Suzuki and for about a week I didn’t hear anything more. So I called him up and asked, how about my translation? Was it OK? No questions or problems?

“No,” he said it was fine. “Just fine.”

“So what was it for?” I asked.

“Oh, they needed it for an art book on the film that’s coming out soon.”

“WHAT!? It’s going into a book? Can I get it back to polish it a little more?”

“No, they’re on a tight deadline. The galley proofs are already locked.”

About a week or two later I got an advance copy of The Art of Princess Mononoke and there, in print, was my rough, awful, crude, awkward, imperfect, first-pass translation, fixed in a published book, there for me to be forever ashamed of.

The studio later decided to use the same English translation as a voice-over for a TV spot for the film. I sat with a deep-voiced British actor in the recording studio as he voiced the lines for the TV spot. After the session the guy said to me, “That was a pretty awful translation. Shouldn’t they have polished it a bit more?”

Rule 2—There will be things that just can’t be translated

The Japanese film is called Mononoke Hime. The English title is Princess Mononoke. The translator (me) has left the two-word title 50% untranslated.

When I first heard the title of the film the word mononoke was completely new to me. This is exactly the kind of word that Hayao Miyazaki likes to use in his titles. It is a word that most Japanese rarely hear or see in print or can even reliably recall the meaning of unless they stop and think really hard about it. It is a word that no two people will define or explain in the same way. The dictionary is no help. It provides things like specter, wraith, or supernatural being, but everyone I ask says this isn’t it exactly. Any attempt to further explain it takes paragraphs. Japanese is full of words like this.

So I decided to just leave it. I assumed that by the time the film came out in English, someone cleverer than me would have come up with a good word (or words) for it. In the nearly twenty-plus years since the film came out, no one has come up with anything.

Rule 3—Sometimes you just have to let go and leave things out

As soon as the final version of a Japanese commercial film is approved for release, the translator or translators begin making an English-subtitled version.

Creating the subtitles is very hard. Your translation has to be accurate. It has to sound natural. And you have to be able to read the subtitles in exactly the same amount of time it takes for the character to say the lines on screen.

This is an example:

In the film Princess Mononoke, Ashitaka, riding his faithful elk-like animal named Yakul, comes upon a battle. As he watches from a hilltop, several of the samurai fighting below notice him. One of them says “Kabuto kubi da!” Direct translation: kabuto—helmet, kubi—neck, da—is. Literally, the samurai has said, “The helmet is a neck.”

Though kubi may literally mean neck, it also refers to a severed head. So “kubi da” refers to a head cut off. Kabuto in this case is just a very quick way of saying “that guy wearing the helmet.” In feudal Japan a soldier often received a bounty for every severed head he brought back from a battle. Proof of an enemy kill.

So the samurai is saying “That guy wearing the helmet, if we cut off his head we get a reward.” That translation made into a subtitle would take eighteen beats. “Kabuto kubi da” is six beats long. Your subtitle translation needs to lose twelve beats. It needs to be 70% shorter.

“Get the guy in the helmet! Take his head!” Ten beats. Still need to lose four beats.

“The helmet guy is mine.” Six beats, so it should be OK. But now the translation sounds funny. What’s a helmet guy? And you’ve lost the head being cut off and taken in for a bounty.

“His head is mine.” Four beats so it fits fine, and as a bonus, slow readers can follow. It feels right in the context, but you’ve given up mentioning the helmet. But it’s a better line. Japanese speakers get the full flavor. English speakers get an abridged yet acceptable alternative.

Rule 4—Don’t take anything for granted

In the film Spirited Away is a scene where it’s reported that the character Haku has stolen the character Zeniba’s seal. The Disney writers working on the English-language screenplay of the film contacted us urgently because they were puzzled by this. In Japan, a seal (an emblem used as a means of authentication) is a very important thing. Americans routinely affix their signatures to checks, credit card slips, and legal documents, but in Japan everyone uses a seal for this purpose. For legal documents and such, a Japanese person takes out his/her seal, presses it into a pad of red ink, and then stamps it onto the relevant document.

The Disney writers wanted to know why, if Haku had stolen Zeniba’s seal (semi-aquatic marine mammal), the seal never appeared in any subsequent scene in the film.

When it comes to foreign cultures, you just never know what other people know and what they don’t.

Rule 5—Review everything.

When we got back the first screenplay for Castle in the Sky from Disney to review, we checked the dialogue over and over again, but we didn’t think to check the characters’ names. It was only later when we began to get samples of recorded dialogue that we noticed that some of the characters had odd names.

Wishing to impart to his film a slightly international flavor, Hayao Miyazaki had given two of the characters French names, Charles and Henri. These names pronounced and written in Japanese come out as Sharuru and Anri. Disney’s translator, who was a third-generation Japanese-American and had never lived in Japan, and who also didn’t believe in asking questions, had decided that the names were probably Chinese. So despite Disney’s frequent complaint that the names in Ghibli’s films were too exotic and hard to pronounce for an American audience, Disney ended up with characters in its version of Castle in the Sky named An-Li and Shalulu when they could have had Henry and Charles.

About the Author

Steve Alpert was a senior executive at Studio Ghibli for fifteen years beginning in 1996. He speaks Japanese and Chinese and has lived in Tokyo, Kyoto, and Taipei. Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man: 15 years at Studio Ghibli (Stone Bridge Press, June 2020) can be

Steve Alpert was a senior executive at Studio Ghibli for fifteen years beginning in 1996. He speaks Japanese and Chinese and has lived in Tokyo, Kyoto, and Taipei. Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man: 15 years at Studio Ghibli (Stone Bridge Press, June 2020) can be