From her flight bag Chiharu Kobayashi drew out a Chanel cosmetic purse and popped its clasp. In front of the mirror she touched up her lashes, eyebrows, then her lips. She examined her teeth and made a mental note to pick up a bottle of Hibiki 17-year in Dubai before the onward leg to Tokyo. Was it only her mother—or did all dentists love malt whisky?

Giggling sounded. Two cabin attendants, immaculate in their midnight blue uniforms and crisp epaulettes, rounded the restroom corner and appeared in the mirror’s reflection. On sighting Kobayashi, their giggles ceased. They bowed respectfully and greeted the woman before them with, ‘Good morning Flight Captain.’

At the coffee kiosk outside, the First, Second and Third Flight Officers afforded her similar reverence, then, together as a single unit, they made their way briskly through the quiet hall towards the boarding gate.

Through the gangway’s porthole windows, Kobayashi glimpsed the A350-900, sleek and gleaming in the Heathrow mist. The sight of the ‘Spirit of Kyoto’ always sent a pang of homesickness through her. And yet, for sentimental reasons, it also set her at ease; Kyoto prefecture was her grandfather’s home.

Outside the aircraft, the First Officer finished his inspection and gave Kobayashi the thumbs up. She stowed her logbook, took a few moments to programme the autopilot and made a final call to Air Traffic Control to confirm weather conditions. Last, but not at all least, she assembled the crew in the galley to wish them well for the flight. It was her ritual; her grandfather had done the same during the Pacific War.

Back in the cockpit, she called the ATC for ‘start-up and pushback’ clearance. She initiated the first of her two Rolls Royce engines, then the second, and after a short taxi to the apron, waited, watching the golden dawn sweeping the fog from the English countryside. The tower gave the all-clear. She moved the thrust levers and felt the big engines respond. With nothing but blue sky ahead and three hundred and seventy kilonewtons of thrust behind, her manicured fingers gripped the throttle, shifted it smoothly forward, and there it was—more than the elation of mastery over machine—that freedom to soar.

The English Channel slid beneath her, the French coastline next, and soon the patchworked farmlands of Normandy were lost to the clouds. She brought the aircraft to 30,000 feet, levelled out and handed over control to the computer. Hot coffee arrived. She cupped its warmth in her hands, marvelling at the sea of altocumulus ahead of her. It recalled the valleylands of Kyoto in winter, when, many years ago, she’d gone to visit her grandfather for the last time.

⁂

A green Toyota made its way along an icy road. Snow-covered fields of rice stalk ran to the base of mountains on each side. At a railway crossing, the car halted and from a tunnel a red two-carriage diesel train burst with plumes of white powder into the bright morning light. Wrapped in a pink bomber jacket and wearing a knit cap, the young girl seated in the back of the car looked sullen; neither the landscape nor the funny-looking train held for her any mystery or intrigue.

The car turned into a driveway and a few moments later stopped outside a large wooden and tiled-roof homestead. Craggy rocks jutted from an ornamental garden. There were stone lanterns, plum and cherry trees, and a pine whose trunk had been coaxed into an archway. To a youthful mind it might have harboured dragons, fairies and goblins. But to the young girl peering out of the car window, it was simply a garden—cold, still and lifeless.

A kitchen curtain ruffled, a face appeared, then was gone. The entranceway door slid back and framed in the doorway a small woman wearing a faded blue smock and apron appeared, all red-cheeks and smiles. The young girl’s mother got out of the car and ran to embrace the old woman. They exchanged greetings then turned around.

‘Chiharu! Come and say hello to your grandmother!’

The car door swung open, the girl got out and walked towards the women. She swung a backpack beside her, dragging its small Totoro figurine in the snow.

‘Who’s this young woman?’ said the old woman. ‘Look how she’s grown! I hardly recognise you from the photos.’ She stepped forward, hugged her, and the small body softened within her embrace.

‘Let me see, you must be nine by now?’ the old woman said.

The girl nodded, smiled shyly.

‘Well come in, come in! Let’s meet your grandfather. He’s been waiting.’

The homestead was warm and dim inside. Kerosene fumes, the aromas of steaming rice and incense fought for air superiority as they moved deeper into the house. Chiharu looked about at the earthen walls, the crooked ceiling beams and the paper sliding doors—so different to her two-bedroom apartment in Tokyo, so quiet and still.

The three of them reached the center of the house and the grandmother slid back a door. Sunlight flooded through the windows and onto the tatami mats of a large living room. The snowbound garden outside seemed otherworldly. In one corner of the room, a sacred alcove held a hanging scroll of a tiger crouching in bamboo; beneath this a set of deer antlers stood with a samurai sword cradled in the horns.

Chiharu’s attention moved to the opposite corner and a purring kerosene heater; a flask of sake bubbling on its mantle. Her gaze was suddenly arrested by a stirring movement at the low table in front of her. She hadn’t noticed the body tucked beneath the futon of the kotatsu. Slowly, it rose and turned.

‘O-tosan,’ her grandmother said, ‘They’re here! It’s Megumi and Chiharu.’

The old man wore a strange leather hat—the kind that Chinese or Russian people wear in winter. Lined with wool, the side flaps curled up like dog ears. The old man’s eyes were watery, his skin ivory-coloured. Though he smiled, he seemed at first not to see them.

The girl’s mother rushed forward to embrace him. They talked in whispers for a short while, her mother tearfully holding his hand, until the grandmother said, ‘And look at Chiharu! The last time you saw her was three years ago, remember?’

The old man turned and studied the girl, and his expression changed, as if something from long again had been suddenly recalled.’

‘Chiharu,’ he said in a raspy croak.

‘Hello Grandpa.’

He motioned her closer, holding out his dry, creased hand until he felt hers, and gripped it.

‘You’re a young woman…’

Chiharu giggled.

‘Would you bring my sake over there?’

‘Don’t be silly!’ said the grandmother. ‘She’ll burn herself.’ The old woman took a cloth from the table, lifted the flask from the heater and carried it to the table.

‘Did you take your medicine?’ Chiharu’s mother asked.

‘This is my medicine,’ he said, fingering the hot flask.

‘How’s your heart?’

‘Still ticking.’

‘Well, just don’t drink too much, alright?’

He nodded, grunting in the affirmative, but winked slyly at Chiharu.

The two women moved to the kitchen, chattering as they prepared refreshments. The old man patted the futon beside him.

‘Sit down here,’ he said.

Chiharu obeyed, tucking her feet into the table’s warm depths beside him.

‘How was your trip?’ he said.

‘Good.’

‘You like Tokyo?’

‘Yes.’

‘You must be an elementary school student now?’

She nodded.

‘You like school?’

‘Yes.’

‘Got a favourite subject?’

‘Science.’

‘I liked science too. When I was young I wanted to be a scientist and build things.’

She said nothing and he leaned closer to her, so that she could smell the land on his body, the sake on his breath.

‘What do you want to be when you get older?’

She smiled shyly.

‘An engineer? A nurse? A dentist, like your mother?

She shook her head.

He reached for his sake cup, an odd-shaped vessel fashioned from brown clay.

‘Would you pour my sake? My hands, they’re a little shaky.’

She lifted the flask, hot beneath her fingers, and poured with precision—not a drop spilled.

‘Well done,’ he smiled, then raised his cup and slurped noisily.

They sat in silence for a while, then she asked, ‘Why do you wear that funny hat?’

‘This?’ He patted the strange headgear. ‘This is the only thing that keeps my head warm in winter.’ He lifted it from his blotchy pink head and placed it on her hers.

‘This is a pilot’s hat,’ he said.

‘I don’t think so,’ she replied.

‘It is, you know. It’s a Japanese Imperial Navy flier’s hat.’

‘Where did you get it?’

‘It’s mine.’

‘It smells funny.’

He chuckled, watching her small fingers explore the creases, the furrows and mysterious lines in the leather, as if tracing routes on an old map. He lifted the sake cup to his lips, drained it, and rose unsteadily to his feet.

‘Toilet,’ he said.

He was gone a long time. From the kitchen Chiharu heard snatches of conversation, words like “divorce” and “separately”, words she’d heard shouted with ferocity between warring parties late at night in their Tokyo apartment. She got up and crossed to a low bookshelf which ran against the wall. Her fingers danced across the volumes of old books, stopped, and plucked one out. She mouthed the title, ‘Taiheiyo Senso.’ She thumbed the soft, worn pages of black and white images and stopped at a double-page spread. For a while she studied the photo carefully: a line of highschool girls waving branches of cherry blossoms at a young pilot readying his plane for take-off on a grass airstrip.

‘Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa.’

His voice startled her. She turned quickly to find him staring down.

‘You know what means?’ he said.

‘Hayabusa? It’s a bird,’ she said.

‘Good, good! Most kids these days think it’s a motorbike or a bullet train…’

‘It’s the fastest bird in the world.’

‘So it is, so it is. You’re very clever.’

‘You really were a pilot?’

The old man seated himself, pulled the kotatsu futon over his legs and again reached for his sake flask. He poured a cup, spilling droplets on the table, and took a sip. He looked outside at the frozen fields.

‘Yes, I was.’

‘You flew the Hayabusa?’

‘No.’

‘What then?’

‘The best plane Japan ever made—a Zero.’

Chiharu turned back to the book and thumbed the pages, but there were no more images of planes, only photographs of dead men on beaches, dirty-faced children and ruined cities.

‘The book with gold letters, see it?’ He pointed to the top shelf.

Chiharu replaced the book and reached up. It was heavy, but with some effort she laid it on the table in front of him.

‘The Mitsubishi Zero A6M5c.’ He lifted the cover and turned the pages. ‘Fast, light—powerful.’

Chiharu moved closer, peering at the images of a plane so simple in shape and design that it might have been an outline in a child’s sketchbook.

At that moment, the two women returned carrying a tray of cups with a teapot on it, and a wooden bowl filled with rice crackers.

‘What’s that, Chiharu?’ said her mother.

‘O-tosan…’ the grandmother said gravely.

‘She’s interested in planes…’ he said.

‘She’s more interested in birds, aren’t you Chiharu?’ said her mother, setting down the tray and pouring the steaming hojicha into small cups. ‘Problem is, in Tokyo there aren’t many.’

‘Yes there are! There are bulbuls and sparrows and crows…’ said Chiharu.

The grandmother passed her the snacks, ‘Help yourself, Chiharu,’ she said. They took their tea and slurped it noisily.

‘Look!’ said the grandfather. The three women turned to the garden, where a small bird with metallic green plumage and a white ring around its eye flitted among the branches of the plum tree.

‘Know what kind of bird that is?’ said the grandfather.

‘Mejiro,’ Chiharu said.

‘That’s right!’ The old man clapped his hands.

‘Funny, I’ve never seen one in Tokyo,’ said her mother.

‘How did you know that?’ said the grandmother.

‘From the library.’

‘Ah yes…of course. That’s where you spend all your time,’ said her mother.

‘What about sports?’ asked the grandmother. ‘Don’t you play table tennis or badminton with your friends?’

‘I don’t have any.’

‘No friends?’ The grandfather looked incredulous.

Her mother sighed. ‘The neighborhood kids are all too busy with cram schools, ballet, violin lessons—’

‘Hooaka!’ Chiharu cried. The adults turned back to the garden. Sure enough, a second bird, larger with a light brown plumage a black-and-white striped head, had joined the first. For a moment they danced madly, loosening plumes of snow powder from the tree branches, and then were gone.

‘They come down from the mountains looking for insects and farm seeds,’ said the grandfather, slipping a rice cracker into his pocket. ‘Chiharu, let’s take a walk shall we?’

The two women stood at the window watching the old man and the young girl set out across the snow covered field. A small Shinto shrine stood at the base of a forested, snow-dusted mountain in the distance.

‘How is she doing at school?’ asked the grandmother.

‘She’s having a hard time.’

‘Poor thing. Why not move back here? Open a practice downtown. Chiharu can visit us.’

‘Kyoto?’

‘It’s cheaper than Tokyo—and there are lots of birds.’

The girl’s mother sighed, her gaze returning to the two distant figures which now seemed to float on a glistening white plane.

‘Sometimes I wish I was a bird.’

⁂

The snow sparkled in the sunlight, mesmerizing the young girl and with each crunching step. She squeezed the old man’s hand and shouted, ‘Wagtail!’, pointing to the shrine up ahead. A persimmon tree grew in its courtyard and about the branches a flittering movement made by a small, bulb-shaped bird with black and white plumage, was visible.

‘You’ve got a good eye,’ he said. ‘Just like a pilot.’

They reached the shrine and entered beneath the torii gate. He pulled a rice cracker from his coat pocket and crumbled it in his hand. He cast the golden crumbs into the air, scattering them over the snow beneath the tree. ‘They’re watching us. You wait, when we’ve gone…’ He looked skyward. Look! A kestrel up there, see?’

Her gaze followed his to a point high over the mountainside where a raptor whirled on the updrafts in slow, graceful arcs.

‘How does it feel to fly, Grandpa?’

‘Free—that’s how it feels.’

‘You were scared?’

‘Oh many times.’

‘Because you might crash?’

‘No.’

‘What then?’

‘Because there were other men up there trying to kill me.’

She looked thoughtful.

‘Come on, let’s go home,’ he said quickly.

‘Aren’t you going to pray at the shrine?’

‘No.’

‘Why not?’

‘I don’t believe in gods.’ He looked back to the sky, but the kestrel had gone. ‘We’ve fed the birds. Now I’m hungry.’

‘Me too,’ she said.

They made a game out of tracing their footsteps back across the snowy field to the house doorstep where they stomped their boots free of snow.

‘Grandpa…’

‘Yes?’

‘Could we build a Zero?’

‘What?’

‘A model plane, like the one you used to fly. We can buy one—I’ll use my New Year’s gift money.’

‘A Zero? Well, I don’t know—’

‘You can help me build it.’

He stood on the threshold, gazing into her face, so filled with innocence and earnestness that it might have been begging for food.

‘No-one’s ever asked me that before,’ he said quietly.

‘I like birds and planes.’

‘So you do,’ he said. ‘So you do.’ He patted her on the head and together they entered the house.

⁂

They stood at the bus shelter the next morning, staring out at a world rendered smooth and formless by the night’s fresh flurries. Mountains, like great big sugar loaves, rose on each side, stark white against the January sky. Icicles dripping from the bus shelter eaves; the sound of running snow melt everywhere. They waited in silence, Chiharu in her pink down feather jacket, the old man in a brown woollen coat and scarf knotted beneath his chin. The bus arrived with its snow-chains rattling and clanking, and soon they too, like the other solemn-looking passengers, peered out at the winter wonderland, each lost in their own private world of thought.

‘I don’t think your grandmother was too happy,’ he said.

‘About what?’ she replied.

‘About us going all the way to the city just to buy a plane.’

‘Neither was mum.’ They looked at each other and giggled.

The valleyland grew wider and wider until a large river appeared and townships and factories sprouted along its banks, and then finally the city reared up, all hustle, lights and noise. They got off at Nishinikaimachi Street in the heart of downtown and the old man took Chiharu’s hand, lead her away from the bright and bustling department stores, and into a covered arcade where ‘old Japan’ somehow still lived and breathed; where elderly shopped for fish still fresh from the Japan Sea and tea leaves from northern Kyoto, roasted and packaged while you waited. They stopped to sample mikan oranges from an old woman outside her fruit emporium; he promised to buy some on his return.

At a chestnut roaster’s stand they stopped to ask directions; a little further on, said the man in the white bandanna and flashing a gold tooth. They arrived outside a corner shop whose sign announced in English, ‘Takata Toys and Stationery’. The grandfather set the doorbell jingling. The interior was dim and stuffy, the aisles narrow and cluttered with toys from another era. To Chiharu, it was a museum.

From behind the counter, an elderly woman greeted them, listened to the grandfather’s question, then directed them to an aisle filled with kit models of battleships, tanks and army men. At the very end they found the aircraft.

‘Chiharu, we’re looking for the Mitsubishi Zero A6M5c…can you see it?’

She pulled out boxes at random, examining each, then sliding it back and pulling out another. She turned it into a quest, a game of matching memory—the picture in her grandfather’s book—with the artist’s painted image on each box.

‘Nakajima Ki-84…’ she said, holding a box up to the light.

‘Hayate,’ the grandfather said. He took it from her and studied the artist’s impression thoughtfully: an aircraft rising from a seaborne carrier, young men waving white caps from its deck against a red dawn sky.

‘Know what Hayate means?’

‘It’s a manga story.’

He laughed. ‘Not in my day it wasn’t. It was a plane. Hayate means ‘fresh breeze’. I flew one at pilot school in Korea. Not as fast as a Zero, but handled well enough.’

‘What about this?’ she said, sliding a second box onto the one he was holding.

‘It’s a Zero alright. But this one’s an A6M3. I flew the A6M5.’

‘This one!’ she said triumphantly, shoving a third box onto the second so that he now had to hold them away from his eyes to focus. Then something changed in his gaze. A tremor passed through his body, causing his hands to rattle the boxes and almost dropping them. His eyes remained fixed on the artist’s impression of two Zero fighters soaring sideways over a mountainous tropical island, an American Liberator bomber tumbling, flaming, into the sea far below.

‘It’s yours, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, yes, it is.’

‘The pilots have the same hat as you.’

‘Yes, they do…’

‘Grandpa, are you okay?’

‘I am. I just remembered something. Something from a long time ago.’

‘We don’t have to buy it, Grandpa…’

‘No. I promised.’ He passed it to her. ‘Let’s get it.’

After they had picked out glue, brushes and a half-dozen small pots of paint, they handed everything to the old woman who set to work on her abacus.

The air outside in the shopping street was frigid. ‘Hungry?’ he asked her. ‘Yes,’ she said, and so they stopped at a dumpling stall and bought six balls of hot battered octopus each, hoisting them into their mouths, and sipping Cokes to cool their burning tongues.

Snow began to fall and as the bus headed back to the valleylands, through the intermittent blizzards, Chiharu dozed against her grandfather; he with his arm around her, his own eyelids growing heavy with the locomotion of the bus as it rejoined the river. The mountains, once again, reared up like great white sugar loaves. At some point the old man’s eyelids flickered and he uttered a murmur, ‘Hellcat on your tail, Ando. Pull up, pull up, you’re too low …’. His face contorted, he lurched awake and screamed, ‘Andoooo!’

He looked about, at Chiharu wide-eyed and staring up at him. The bus driver, who had pulled over, and passengers all watched him curiously. ‘Sir, are you alright?’ the driver asked over the speaker system. The old man took a deep breath and exhaled slowly; he nodded, bowing his head. ‘I’m sorry.’

At the bus stop, the mother and grandmother were waiting for them. Inside the car their voices comforting, their inquiries soft and quiet. Chiharu looked at her grandfather, who quickly put a finger to his lips.

After dinner they sat at the kotatsu, watching TV. Chiharu took out the box containing the Zero.

‘What’s this?’ her mother said, frowning. ‘I thought you were going to buy an All Nippon Airways jet.’

‘That mightn’t be such a good idea,’ the grandmother chimed in. ‘For a small girl…’

‘The Zero A6M5c’s maximum speed was five hundred and sixty-five kilometres per hour. It could fly to eight thousand metres in nine minutes and fifty-seven seconds,’ said Chiharu. ‘The Americans called it ‘Zeke’…’

The two older women exchanged glances; they turned to the grandfather, who quickly picked up his sake cup and drank it dry.

Later, as Chiharu lay beneath the heavy futon in the guest room nextdoor, she heard her mother speaking in hushed tones to her grandfather. Snatches of conversation that, even if she could not understand, were plainly clear by their tone; words like, ‘psychological trauma’, ‘dark memories’ and ‘unsuitable for a young girl’. And the quiet rebuke of her grandfather, that the child showed a passion for ‘flight and flying machines,’ that he was once a pilot and he understood this better than anyone…But it was her mother who had the last word. ‘I do not want her hearing old war stories—or building machines of war. She’s a nine-year-old girl for goodness sake!’

Chiharu rose the next morning to a house becalmed. Snow fell in steady veils across the fields outside. She found her grandfather seated at the kotatsu, the flaps of his flier’s hat pulled down over his ears and a flask of sake steaming on the kerosene heater. Spread haphazardly over the table in front of him was a thousand-and-one-piece jigsaw puzzle.

‘Where is everyone?’ she asked.

‘Farmers’ market. Shopping for dinner,’ he said.

‘What are you doing?’

‘Building Kinkakuji—The Golden Pavilion. Want to help me?’

‘Why don’t we build the plane?’

‘I don’t think it’s a good idea. Your mother—’

‘We don’t have to tell them.’

Her gaze held his, and there it was again, that intense look of earnestness and determination. It was too much for him to bear. A conspiratorial smile worked to his lips, as he pulled the box from its hiding place under the kotatsu and placed it on the table.

‘Trouble is, my eyesight is bad and my fingers shake. You’re going to have to help me.’

She joined him on a cushion at the table.

‘The A6M5 Zero was the Imperial Navy’s best fighter plane in the Pacific War,’ he said, producing a small pair of scissors.

‘I painted the pieces last night, after everyone had gone to bed,’ he said.

‘What about the plans?’ she asked.

‘Don’t need plans—I know this plane by heart.’

He passed her the scissors.

‘You can cut out the pieces.’

In a short time, the table top was covered with them, and Chiharu looked with uncertainty at her grandfather.

‘I think we need the plans, Grandpa—’

‘Don’t need plans. I used to fly this, remember? Just follow my directions.’

The snow continued to fall silently, surely, across the mountains, fields and valleylands as they commenced, piece by piece, to assemble the aircraft.

‘This is a Nakajima ‘Sakae’ engine. Eleven-hundred horsepower,’ he said, passing her three round silver disks. ‘Thread these onto the propellor shaft,’ he instructed her. Next, he handed her a set of curled silver-coloured pipes. ‘This is the exhaust propulsion system. Gave a top speed of five hundred and sixty-five kilometres per hour…but you know something? I clocked five-eighty-five once over Rabaul in…let’s see now, that was May 1942.’

‘Where’s Rabaul?’

‘In Papua New Guinea. Right above Australia.’

‘You shot someone?’

‘No, no—I was escaping! One of my guns had jammed, the other was out of ammunition’

He picked up two long black-painted gun barrels. ‘The Zero A6M5 had two seven-point-seven millimetre machine guns and two twenty millimetre belt-fed cannons on each wing,’ he said, holding them away from his eyes. He passed them to her, hands shaking. ‘Now glue the holes in the middle of each wing section and insert these.’

‘Did you travel the world, Grandpa?’

‘During the war?’ He chuckled. ‘Oh, no, no. But I saw more than enough of it, let me tell you. When I was seventeen, I went to the Imperial Navy college in Mie prefecture, and after that to Korea for pilot training. Then I joined the Tainan Air Group and we flew in China, New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. After that, I was sent to Yap. You know it?’

She shook her head.

‘It’s a tiny island in Micronesia…’

‘In the Pacific Ocean?’

‘It was beautiful…’ A sudden spasm reached his throat. He coughed, harked, took tissue from the holder and wiped his mouth. ‘But war doesn’t care for beautiful things. The Americans were getting closer and I was eventually sent home to defend the country’ He passed her the left and right wheel units. ‘You know where these go, don’t you?’

She nodded, applied glue to the wing cavities and inserted each wheel strut. He continued, ‘Our name was changed to the 251 Air Group and many of us experienced fliers were ordered to train the younger pilots. I went to Kure.

‘Near Hiroshima?’

‘Yes—Don’t forget the antenna, it goes in that tiny hole near the wing tip.

‘Did you shoot down many planes?’ she asked matter-of-factly, while skillfully pushing the black needle into its hole.

‘Yes.’

‘Why?’

‘Because that was my job. I did it because I had to.’

He rose slowly from his cushion and took the steaming flask of sake from the heater’s mantle. He returned to the table and poured his cup full. He raised it to his lips, drops sprinkling the table, until it was dry. He wiped his mouth with the back of his hand and said, ‘You’ve done well. Now attach the wings to the body and we’re almost done.’

‘Is that why you had a bad dream on the bus yesterday?’

He poured another cup of sake and, as if to fortify himself, took a sip.

‘We were fighting for our lives by war’s end. I was an instructor, but I flew with our group because we had only eleven pilots left. Just boys, they were. The Americans were close and our losses were terrible. One day we took off, four of us, heading south for Kyushu and I got engine trouble. I turned back, had the engine fixed, and joined the second four Zeros on the runway. But as we prepared to take off, we were attacked. Corsair fighter planes from an American carrier swooped in over the hills, hit us while we were still on the ground. Ando, the Master Sergeant, was shot down on take off. I survived only because I was last in line. I jumped from my cockpit and ran. My plane was hit right after that.’

‘What about the other pilots?’

‘The first three? They never came back. Everyone else was killed…except me.’

He rose from his cushion.

‘Grandpa, where are you going?’

‘I forgot to give you the most important part of the plane—the pilot.’

He returned carrying an old paulownia wood box which he placed on the table. Then he opened it and drew out a folded piece of red and white cloth. Chiharu watched curiously as he spread it across the table.

‘Hinomaru,’ she said quietly, eyeing the old flag. It was covered in the names of men.

‘Those are all the pilots in my group. Fifty-five men. They’re all gone now…’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I’m the only one still alive.’

He took from the box another item—a wristwatch.

‘This is my flier’s watch. It’s a Seikosha. I think it still works. Let’s see…’ He twisted the crown several times and the second-hand leaped forward. ‘It does!’ he said and passed it to her. ‘This is for you. For helping me build the plane.’

‘But you were helping me,’ she said with wide eyes.

‘Oh no!’ he said looking beyond her, out the window. ‘Here they come!’ She followed his gaze, and in the distance, spied the small Toyota now making its way up the long driveway towards the house. ‘Hurry, put everything in the box. We’ll hide it under the kotatsu.’

‘But where’s the pilot?’ she said quickly.

‘Oh, I almost forgot. Here,’ he said. He pulled from his pocket a small figurine and placed it in the palm of her hand. She stared at it, and said. ‘But why did you paint him with a pink jacket?’

‘Because it’s not a ‘him’, it’s you.’ He smiled. ‘Now hurry up, put it in the box before they see.’

She obeyed, and together they quickly cleared the table.

When her mother and grandmother appeared, they were still huffing and puffing from the weight of the fresh produce boxes they had brought into the kitchen. Sliding back the door to the living room, their expressions turned to surprise.

‘What’s this? All this time and you haven’t even started the jigsaw puzzle?’ said her mother. ‘What have you two been doing?’

‘Just talking,’ Chiharu said.

‘About what?’

‘Flying.’

The grandfather turned back to the window and gazed out at the sunlight now casting through the snow clouds directly onto the roof of the Shinto shrine. It looked almost heavenly.

⁂

A shrill scream split the dawn.

Chiharu listened to the sound of hurried steps, moving between rooms, and then the grandmother’s voice into the kitchen telephone, requesting an ambulance.

He had died during the night. Of heart failure, said the doctor—but peacefully. There was nothing that could have been done. What had seemed strange to them all was the paulownia wood box which had been placed at the foot of Chiharu’s futon. Inside, a note written in his hand read,

‘To Chiharu,

May your spirit soar—always.

Your Grandpa.’

Only after the ambulance had pulled away and begun its descent of the valley road, did the mother and grandmother notice her missing. They hurried inside, calling her name, but there came no answer. Then, through the lounge window, they glimpsed a small figure wearing a flyer’s hat and scurrying across the white field. Tied about its neck like a cape, a piece of red and white cloth billowed. Its hand, raised high into the freezing air, held in it what looked like a small airplane.

⁂

‘Captain, are you alright?’ The voice sounded beside her. Chiharu Kobayashi jerked upright, still clutching her coffee cup. She looked up at the Third Officer.

‘Yes, yes, I’m quite alright,’ she said, wiping the tears away with her hand.

‘May I take your cup?’ he asked.

She thanked him, then turned back to her console to confirm that all was well with the Spirit of Kyoto. With the altocumulous far below them, the morning sky stretched blue and unfathomable ahead of her. She drew back the cuff of her shirt and examined the old Zero flier’s watch.

It was still ticking.

About the Author:

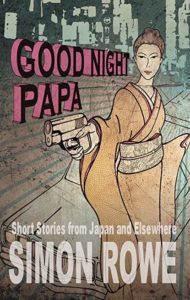

Simon Rowe’s stories have appeared in TIME (Asia) magazine, the New York Times, the Australian, the South China Morning Post and the Paris Review. He is author of Good Night Papa: Short Stories from Japan and Elsewhere.