The History of Comics and the Graphic Novel

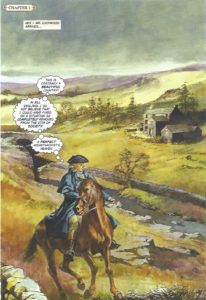

What are comic books (manga) and graphic novels? They are the combination of images and text. Essentially that’s it. What, on theoretical grounds, would place an age or sophistication limit on something that combines image and text? Are, for example, road signs – which are normally a combination of image and text – only meant to be read by teenage road users? Clearly not. It would be an odd idea to suggest.

Even comic book creators like myself have to admit, however, that for most of the history of the art form of comics/manga, they have been created with younger readers in mind. But, the audience normally targeted by the producers of an art form is quite different from that art form’s potential and inherent characteristics. We might as well say that music is inherently for kids because most pop music is targeted at teenagers. To extrapolate that ‘music is for kids’ seems ridiculous, even laughable. There is nothing inherent in comic books that dictates they are for younger readers or that they are lowly in artistic value. Instead, we should recognize that there are comic books for children and comic books for adults, just as there is music for children and music for adults.

Comic books have a long history. In the US most scholars place the roots of comics in the 1890s with The Yellow Kid. In the U.K. scholars place them further back, to Ally Slopers Half Holiday in 1867. Some recent research in my home country of Scotland puts their origin even earlier, claiming that The Glasgow Looking Glass (1826) was the first comic strip. Given that Scottish creators such as Grant Morrison and Alan Grant have contributed so much to comics in the last 30 or 40 years, it would be a fitting origin to the art form to have Scottish roots.

Whatever the origin, comics have a long and varied history, stretching over different periods and places, including Japan. In this long flow we have seen developments in the audience, the type of people who make comics, the subjects covered, and the printing and distribution methods. At various points in that history the main target audience for comics were kids and teenagers. But at other times the focus was more on adult readers or a general audience. We are in such a period now, that started in the mid 1980s.

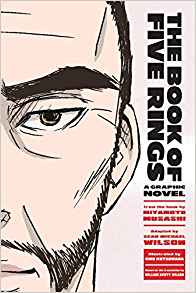

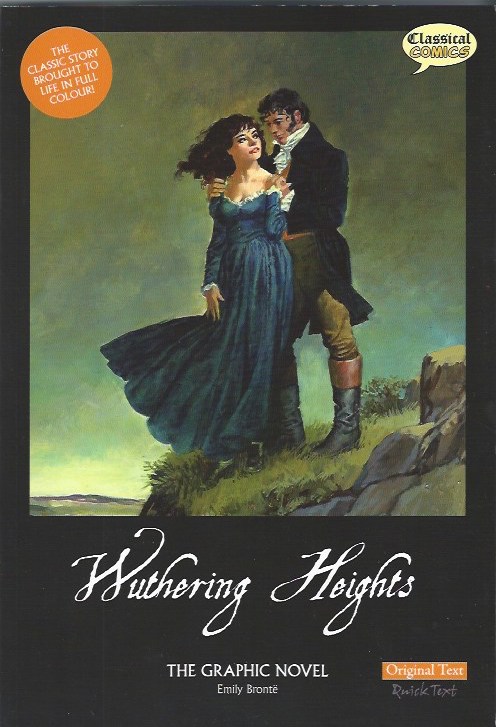

Increasingly, and especially in the last 15 or 20 years, the image of comics is changing. Comics were rebranded as ‘graphic novels’ in order to indicate the increasing sophistication of comics and their suitability for adult readers. Comic books have also become more prominent in public and college libraries, often in dedicated graphic novel sections. Courses in comics are taught in sociology, literature and art degrees in universities and there are even special degrees in comic studies. Many mainstream book publishers have branched out into graphic novel imprints, such as my own US publisher, Shambhala Publications, known for its range of books on East Asia. Comics have also broken into the world of literary awards. In the USA, the long running ‘Independent Publisher Book Awards’ has two categories for graphic novels, alongside the categories of travel books, design, modern history, etc.

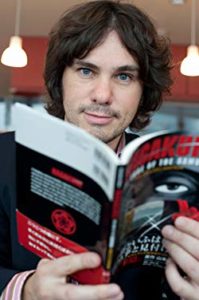

The late 30s to the early 50s is often referred to as the ‘golden age’ of comics. But, looking at it another way we might say we are in a golden age right now. Over the last 10 to 15 years there has been a renaissance in the comic book world in the UK and North America. We have seen the breadth of subject matter and type of creators expand dramatically. There has been a substantial increase in the number of female creators, and in the number of creators from the Middle East, Asia, and Africa in English translation (and French, Spanish, Italian, and others). The range of topics has expanded from the customary subjects of superheroes, comedy, and sci-fi to embrace documentary, history, sociology and intimate portraits of dealing with disease, trauma and war. My own books are often about elements of Japanese history or global society, such as my book with Akiko Shimojima, Secrets of the Ninja, which received an award from the Japanese Foreign Ministry. Another book on alternatives to capitalism, Parecomic, features an introduction by Noam Chomsky, the first involvement of the renowned intellectual with comic books. Our illustrated sociology book, Portraits of Violence, won a literary award and garnered a review in The Times Literary Supplement.

A stubborn level of resistance to the value of comic books persists among fans of literature and art. At a writers convention at a university in Kobe I had a heated debate with a professor who insisted that ‘books don’t need visuals’. He is, of course, right. Novels, ‘regular books,’ text-only books don’t need the illustrations that comic books have. But that is a little like saying spaghetti bolognese doesn’t need Parmesan cheese. Sure, it does not – but if we decide to add it, then without question, something is gained. Regardless of whether it’s to your taste or not.

Comic books inherently bring that mix of text and images, something that regular books do not have. That mix of ingredients gives them something unique which, as readers, we can appreciate and enjoy the taste of. Books have different aspects, which produce different experiences each of which is interesting in it’s own way, for readers of any age. So, I urge you to dip your fork into the taste of the wonderful mixture of text and art found in comic books and manga.

Sean Michael Wilson is author of the graphic novel Wuthering Heights.

He can be found online at:

Web Page: http://seanmichaelwilson.weebly.com

Blog: http://sean-michael-wilson.blogspot.com/

Twitter: @SeanMichaelWord

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/seanmichaelwilson/